| |

This is the homepage of Ane Bysted.

I live in Lunderskov, Denmark, and I have a Ph.D. in medieval history and an MA in the history of ideas.

Most of this site is in Danish, but for the convenience of non-Danish visitors I have translated a part of the contents here on this page.

My Ph.D. thesis was on the indulgences granted for crusades. The title of it is "In Merit as well as in Reward. Indulgences, Spiritual Merit, and the Theology of the Crusades, c. 1095-1216".

It is published as: The Crusade Indulgence. Spiritual Rewards and the Theology of the Crusades, c. 1095-1216.

(Brill 2014, ISBN 978-04-28043-4)

Read more about the book here.

A full list of my publications can be found here.

The first indulgences were granted around 1035 to people who would visit or give contributions to certain churches in Northern Spain and Southern France. In 1095, when Pope Urban II proclaimed the First Crusade he granted the crusaders a plenary indulgence, and all later crusades were caracterised by the grant of indulgences to the participants. Until 1300, when the Roman Jubilees were instituted, plenary indulgences were only granted for the crusades.

The selling and buying of letters of indulgences belong to the later Middle Ages and proliferated especially after the middle of the 15th century and the invention of printing.

How indulgences work

An indulgence is a remission of temporal punishments for sin, i.e. of penances or of punishments in Purgatory. Originally, they were understood as remitting a specific part of the penances one had already been assigned by one's priest. Thus, an indulgence of 40 days meant the cancellation of 40 days of fasting, for instance. Likewise, a plenary indulgence meant the cancellation of all the penances one had already been assigned. Later the indulgences came to be understood as direct remissions of time in Purgatory as well.

The theory of how indulgences worked was only formulated after they had been practised for almost two centuries. In the course of the 11th and 12th centuries theologians such as Peter Abelard, Peter the Chanter, William of Auxerre, and Thomas Aquinas discussed the terms of them.

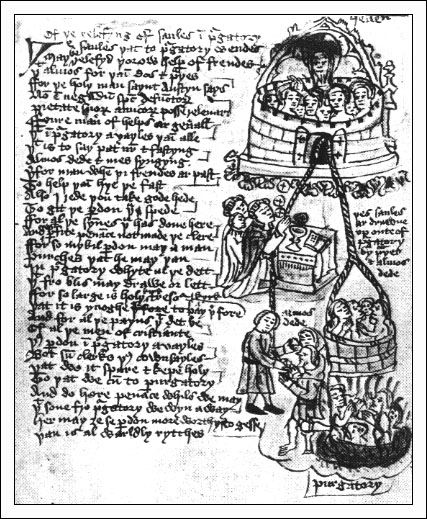

The theology of indulgences remained a rather complicated matter, but this is an illustration of how they were supposed to work in the high Middle Ages.

At the bottom we see the souls in Purgatory, who are cleansed in fire. They can be drawn out of the fire and into Heaven by the help of good works, as for instance giving alms to the poor, and by the intercession and masses provided by the priesthood. Click on the picture to see a larger version.

At the top we see the heavenly castle, or the heavenly Jerusalem, where the saved souls rest in the compagny of Christ.

Please notice the cord drive by which the souls are drawn up to Heaven.

Crusade indulgences

Another good deed that could earn indulgences was going on crusade. This was instituted already for the First Crusade in 1095, and at all later crusades the participants who put their life at risk out of devotion to the faith would gain a plenary indulgence.

From the 1180's it was also possible to gain a crusade indulgence for sending money or arms to the crusade. These indulgences, however, were not plenary but partial in proportion to the contribution. In 1198 Pope Innocent III instituted the indulgence for sending a substitute on crusade. Thus, people who were too old or otherwise unable to fight could send a substitute - and gain a plenary indulgence for that, if they paid for a certain period of service. The substitute himself would gain a plenary indulgence as well.

Letters of indulgences

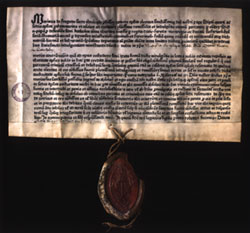

Below is a letter of indulgences from 1475. It was issued by the Italian Marinus de Fregeno to the Danish nobleman Otto Nielsen Rosenkrantz.

The letter belongs to the Danish Royal Library.

Further reading

Ane L. Bysted: The Crusade Indulgence. Spiritual Rewards and the Theology of the Crusades, c. 1095-1216, Leiden 2014 (Brill Academic Publishers, www.brill.com/products/book/crusade-indulgence, ISBN 978-04-28043-4)

Ane L. Bysted: "Remission of Sins or of Penances?: The Meaning of Crusade Indulgences before and at the Fourth Lateran Council" in The Fourth Lateran Council and the Crusade Movement. The Impact of the Council of 1215 on Latin Christendom and the East, eds. Jessalynn L. Bird & Damian J. Smith, Turnhout 2018 (Brepols Publishers, Outremer 7, ISBN 978-2-503-58088-3), pp. 41-57

Ane L. Bysted, Carsten Selch Jensen, Kurt Villads Jensen & John H. Lind: Jerusalem in the North. Denmark and the Baltic Crusades, 1100-1522, Turnhout 2012 (Brepols Publishers, Outremer 1, ISBN 978-2-503-52325-5)

Nikolaus Paulus: Geschichte des Ablasses im Mittelalter, vol. 1-3 fra 1922-1923. (Is still the major monograph on the history of indulgences and was reprinted in 2000.)

Bernhard Poschmann: Der Ablass im Licht der Bussgeschichte, 1948

Herbert Vorgrimler: ”Busse und Krankensalbung”, Handbuch der Dogmengeschichte, 1978, vol. IV, f. 3.

Bernd Moeller: "Die letzen Ablasskampagnen. Der Widerspruch Luthers gegen den Ablass in seinem geschichtlichen Zusammenhang", Lebenslehren und Weltentwürfe im Übergang vom Mittelalter zur Neuzeit, 1989, s. 539-567

Robert W. Schaffern: ”Images, jurisdiction, and the treasury of merit”, Journal of Medieval History 1996, vol. 22, nr. 3, s. 237-247

Catholic encyclopedia on "Indulgences"

The Code of Canon Law of the Catholic Church on Indulgences

| | |

|

E-mail

My profile on

LinkedIn

The text on this page is copyright Ane Bysted 2022. All rights reserved.

|

|